Nuclear Information Centre.

The Toxic Archive.

NIC/TE/011(2024 - work in progress)

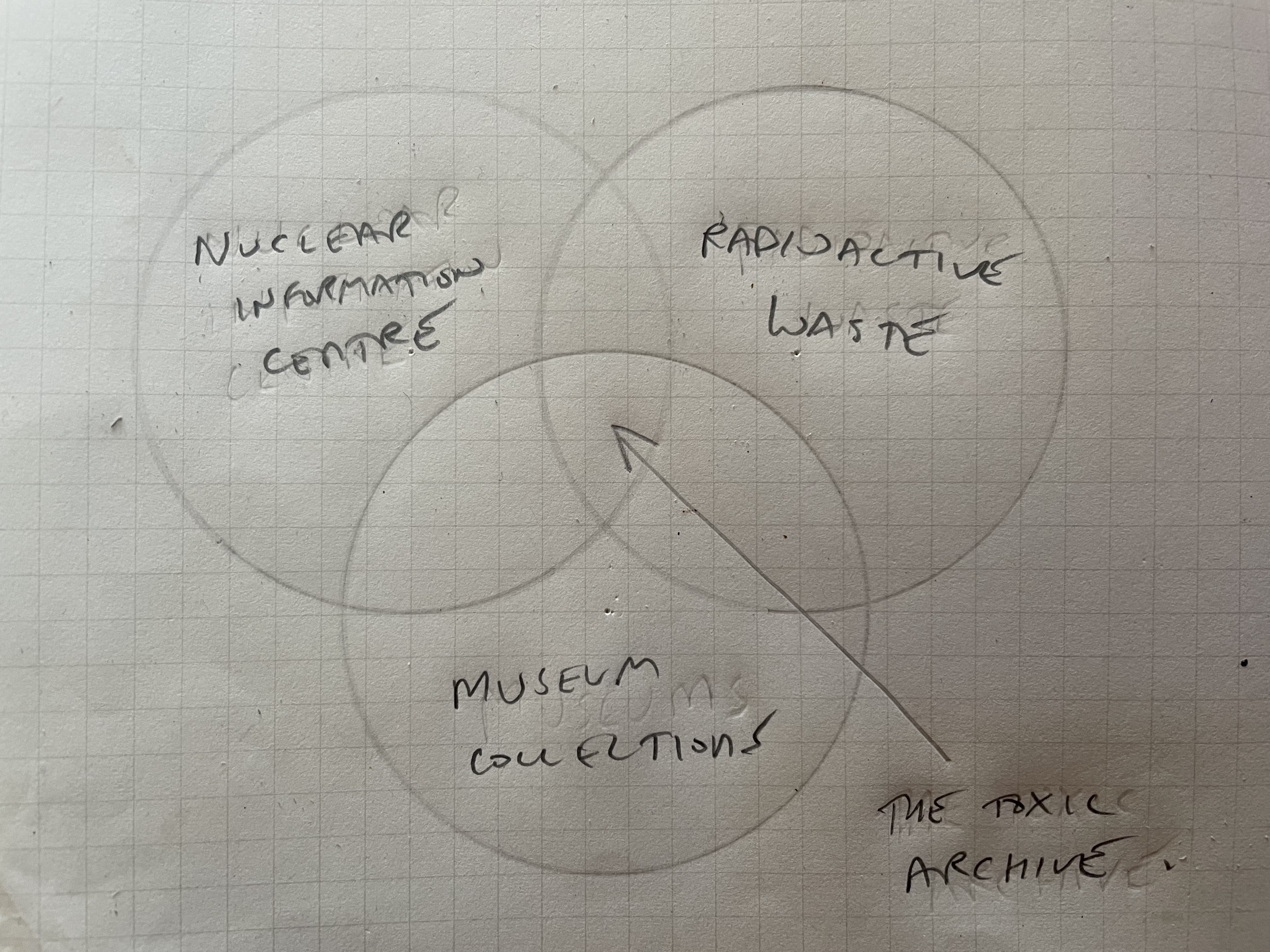

The Toxic Archive is conceived as a slowly evolving research project exploring speculative parallels and entanglements between the ongoing management of radioactive waste and museum collections. Fusing fact and fiction through ambiguous narratives and curated displays, the archive time travels back and forth, creating part engineered, part haphazard encounters with real and imagined nuclear infused objects whilst tacitly raising questions around curatorial selectiveness and cultural heritage within the realm of “the museum”.

Notes.

The first item to be accessioned into The Toxic Archive is in the form of an exhibit entitled The Half-Life Afterlife which comprises recently discovered, ancient looking radioactive waste burial charms from an unspecified future time. These objects have been subject to speculative research methods before being catalogued and displayed in a very human attempt to imbue them with cultual significance, revealing important clues about our toxic nuclear past. Following display, the objects themselves may be earmarked for de-accessioning and disposal, echoing the fate of the buried nuclear waste they were created to accompany.

Resources.

Notes from the Museum Association (Off the Shelf: A Toolkit for Ethical Transfer, Reuse and Disposal):

If museums are to be financially and environmentally sustainable, and relevant to the communities we serve in the 21st century, we must take an immediate and proactive approach to collections management and review.

Ethical transfer, disposal, reuse and deaccessioning are everyday and necessary parts of a sustainable collections management approach and the need for this work is urgent. Museums must do their part to address the climate crisis for the benefit of society through their collections management practices. Museum stores can have a significant number of items which have low cultural or research value.

If these items are not being used then it is important that resources and capacity are redirected to other parts of the collection.

Museums hold their collections in trust for the public and have the responsibility of managin and preserving them for use now and in the future. Museums also have a responsibility to ensur that their collections remain relevant and manageable. Removing items from museum collections is vital to ensure that museums are able to maintain and create relevant and dynamic collections, while avoiding becoming a permanent store for items which no longer meet the needs of the communities they serve. (p.4)

Decisions to remove an item from the collection should be made by the museum’s governing body, acting on the advice of relevant staff or must have been made through a system of delegated authorit for deaccessioning decisions. Decisions to remove must not be made by a member of staff acting alone. The final decision relating to the deaccessioning of an item shoul be approved by the governing body directly or through a process of delegated authority and documented.

Damaged and hazardous items

— Is there a value in the item in its damaged or dangerous condition?

— Has the hazard become unmanageable to the extent that there a risk to people or other items if it is retained in its current condition?

— Can the item be repaired or made safe and if so can your organisation afford to do this or fundraise for this in the near future?

If an item is damaged and irreparable, you are able to deaccession it. If it might be repaired and used by another organisation you can consider transferring it – more details of this can be found in in methods of transfer, reuse and disposal section. If you are unable to manage any risk to people or other collection items by retaining the item you have a responsibility to either treat the item in order to remove the risk, manage the risk properly or destroy and dispose of it safely.

Note that it is unethical to intentionally allow an accessioned item to degrade beyond repair in order to dispose of it.

Unethical decisions to deaccession an item can have significant consequences for a museum.

These are likely to include:

- loss or damage of public trust in all museums

- adverse publicity and long-term negative perceptions of the museum

- removal and exclusion from the Accreditation Scheme

- disciplinary action from the Museums Association (if a member)

- loss of access to funding streams.

As with all areas of museum practice it is important that you ensure transparency and openness with the public, colleagues and stakeholders when you undertake deaccessioning of collections. You should think about how you can use your communication channels to consult with the public around the process.

Good, proactive communication will increase the public’s understanding and awareness of this area of museum practice. You should adopt an open and honest approach that explains the context and potential benefit of the planned course of action. You should carefully consider the use of language avoiding any jargon that could cause misunderstanding over the final outcome of the process (for example the use

of terms such as disposal on its own is often misunderstood). It is important to set out publicly the museum’s overall policy on deaccessioning against which individual cases can be explained.

The level, approach and timing of any communication will depend on the nature of the items being disposed of. The whole workforce, including those not directly involved in the deaccessioning process, should have an understanding of your museum’s policy and process, and – for high-profile individual cases – they should also understand the reasons

behind any decisions and any proposed course of action. This will help to ensure that the process is communicated accurately to those outside the museum. You should also consider ways of communicating information to key stakeholders such as Friends of the museum and regular visitors. This could include briefings posted on websites and in newsletters.

If your deaccessioning process has a particularly positive outcome for the wider public you might want to consider ways to publicise the work more, for example by highlighting it to the Museums Journal so that others in the sector might learn from the work.

Back