Nuclear Information Centre.

A Selective Glossary.

NIC/TE/009(August 2023)

Abbreviations.

Abbreviations are used extensively within official nuclear information [1]. Here is just one example:

NWS - Nuclear Waste Services

NWS - Nuclear Weapons State(s)

Ambiguity.

We are deliberately ambiguous about precisely when, how, and at what scale we would use our weapons. This ensures the deterrent’s effectiveness is not undermined and complicates the calculations of a potential aggressor. (UK Government).

Anthropocene.

As a geological descriptor for a new epoch, originally conceived at the turn of the millennium to define the impact of human initiated changes on the fabric of Earth, the Anthropocene has subsequently seeped into cultural consciousness. Within nuclear culture this is particularly evident around considerations of radioactive waste and contamination. In 2015, for example, Ele Carpenter [2] delivered a lecture entitled The Nuclear Anthropocene which was reprised the following year as a short essay in the Nuclear Culture Source Book (edited by Carpenter) which itself was a collective bringing together of nuclear related scholarly writing and creative practice within a single publication. A touring exhibition Perpetual Uncertainty: Art in the Nuclear Anthropocene [3] accompanied the book’s publication.

NIC exhibit NIC/GD/005, What about the Waste? specifically addresses issues of radioactive waste as the UK seeks to construct a geological disposal facility (GDF) for the permanent containment of its most highly radioactive spent nuclear fuel and other waste materials. This exhibit also takes us into the realm of hyperobjects, a cultural by-product of the Anthropocene which asserts that invisible, seemingly intangible objects such as radiation can be considered objectively despite being “things that are massively distributed in time and space relative to humans” (Morton, 2013, p. 1).

Timothy Morton also contributed a short essay to the Nuclear Culture Source Book entitled Radiation as Hyperobject (Morton, 2016). In this text, he considers relationships between hyperobjects, and the visual arts in his own “fabulously textual” (Derrida, 1984) writing style, with affectual turns of phrase such as “Nuclear radiation burns through our concepts of time and space” (p. 172) and “We bristle plutoniumly. Or we feel suicidal plutoniumly. Or we cry plutoniumly. Or we even dance plutoniumly” (p. 173).

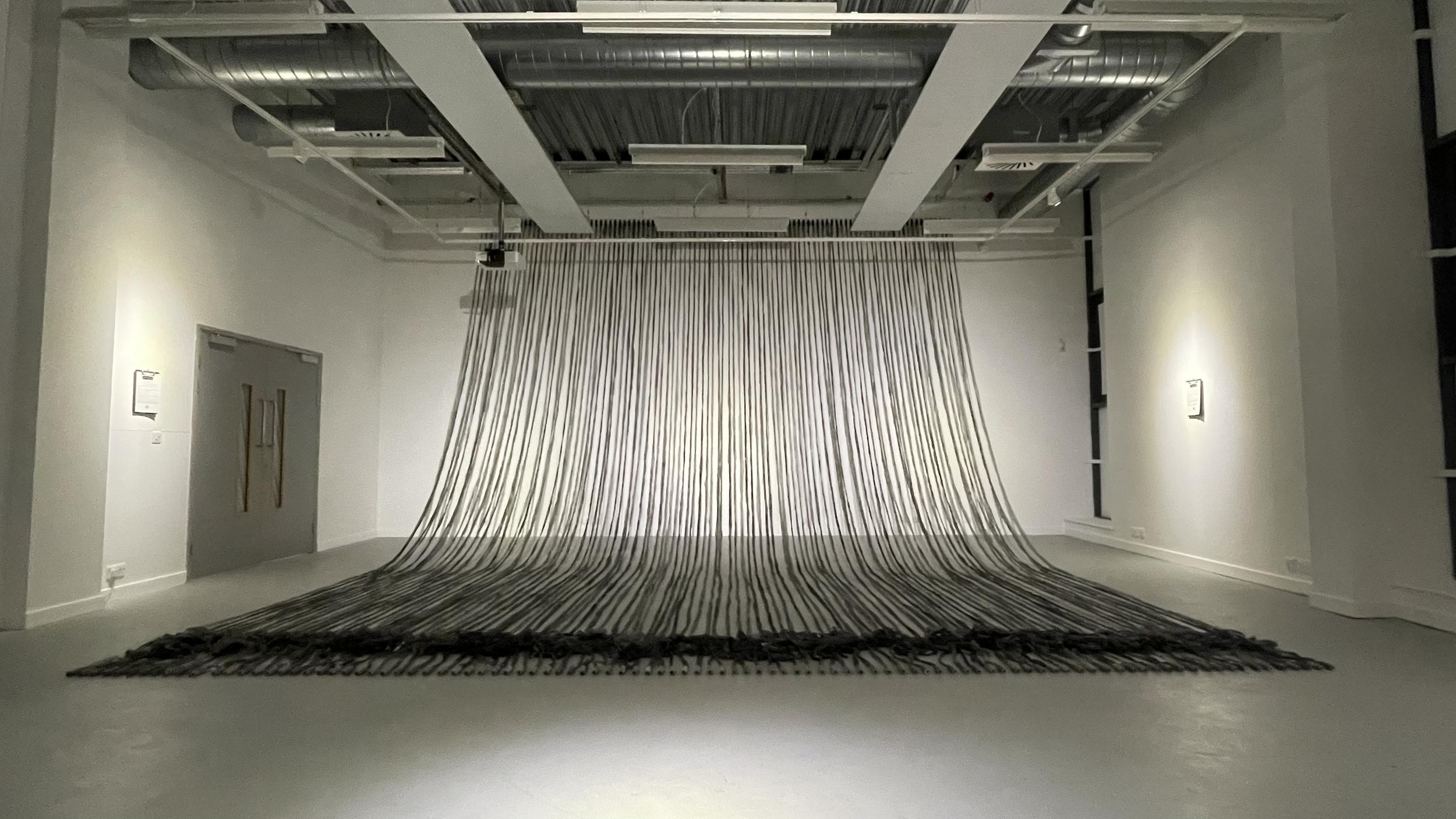

Figure 2. Nic Pehkonen, What about the Waste?, 2022.

G a p s.

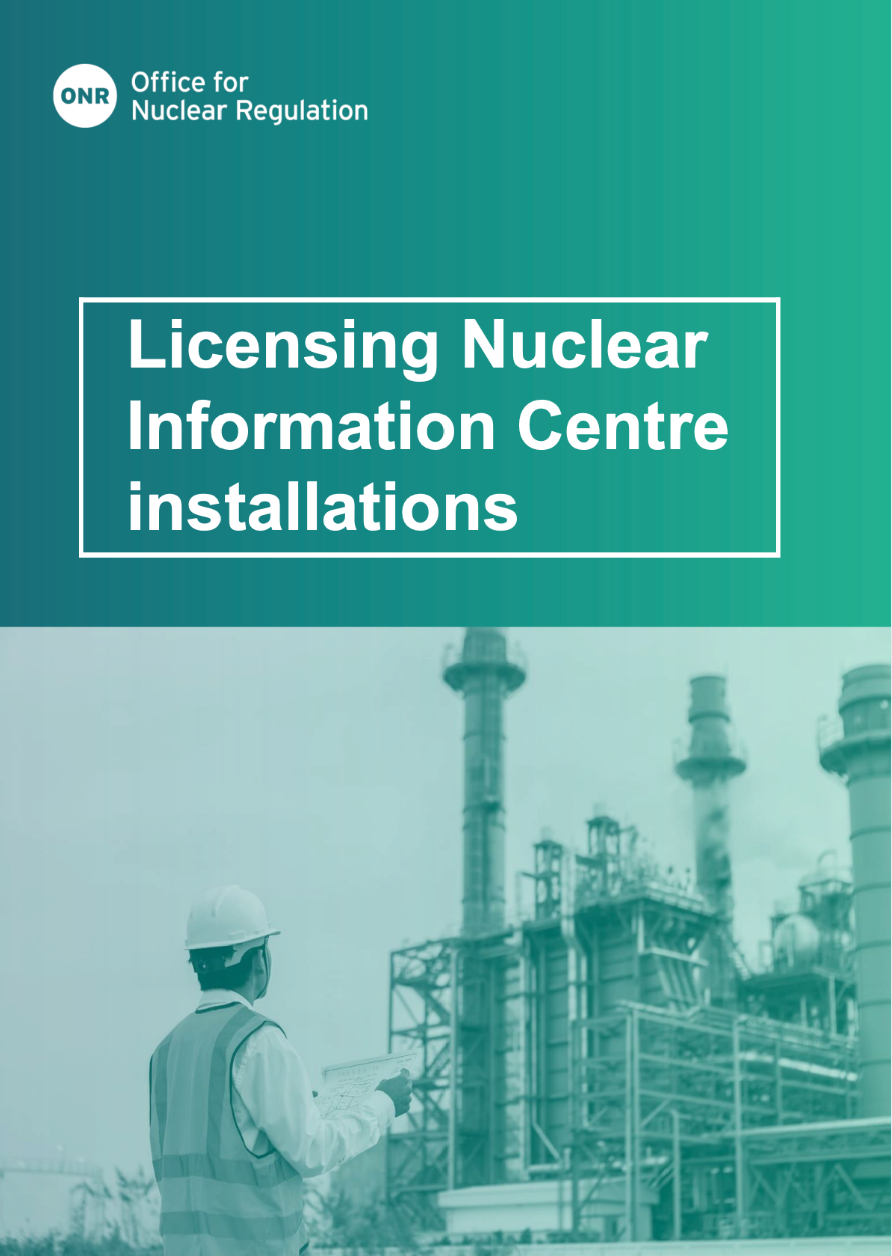

What is not there? What is not being said? Can engineered physical spaces or gaps within text, audio and

even physical objects, influence our reading of the content? This is tested out in the NIC textual exhibit,

NIC/TXT/007, Reading between the Lines (1958-2022) (see figure 3), which places two pieces of text on

the twin subjects of nuclear power and nuclear waste on a single white A4 page with a large blank space

between the two. The top section of text dates from 1958 with the extract at the bottom of the page

originating in 2022. The premise of this exhibit is to create an imaginary, blank timeline traversing the

physical space between the two dates that tests to what extent our mind tries to fill the gap based on our

readings of the two sections of text. Do we ignore the space, or do we unconsciously find ourselves trying

to fill it and if so, with what?

even physical objects, influence our reading of the content? This is tested out in the NIC textual exhibit,

NIC/TXT/007, Reading between the Lines (1958-2022) (see figure 3), which places two pieces of text on

the twin subjects of nuclear power and nuclear waste on a single white A4 page with a large blank space

between the two. The top section of text dates from 1958 with the extract at the bottom of the page

originating in 2022. The premise of this exhibit is to create an imaginary, blank timeline traversing the

physical space between the two dates that tests to what extent our mind tries to fill the gap based on our

readings of the two sections of text. Do we ignore the space, or do we unconsciously find ourselves trying

to fill it and if so, with what?

Figure 3. Nic Pehkonen, Reading between the lines, 2022 [Note: you are looking at an image of text].

Figure 3. Nic Pehkonen, Reading between the lines, 2022 [Note: you are looking at an image of text].Humour.

Humour is a critical element within the NIC informational stockpile, and its use should not be underestimated as a powerful, affectual tool for addressing nuclear issues, which in themselves may stir strong emotions, whether that is through lived experience or the imagination (Henwood, Parkhill, Pidgeon, Simmonds, 2011). Humour can be disarming and socially inclusive which affords it significant value as a serious method of audience engagement. For example, there is an intentional light-heartedness present in NIC exhibit NIC/GD/003, Nuclear Football which tackles the thorny subject of locating a site for the permanent disposal of the UK’s higher activity radioactive waste in a (literally) playful way. It is an actual football, specifically designed to be played with. In this exhibit, the ball becomes a metaphor for the as yet unidentified GDF site insofar as it can be kicked/passed around with no fixed resting place.

Figure 4. Nic Pehkonen, Nuclear Football, 2022.

Messiness.

Nuclear realities are messy. Official nuclear information exists to tidy things up although, despite its best efforts, there is never a shortage of lines for us to read between. Nuclear activity exists in a state of constant tension between extreme order and disorder. The precision and rigour of nuclear science and technology is always accompanied by the ever-present threat of war and the realities of accidents, contamination, and ongoing conundrum of safely managing radioactive waste. Any critical examination of current nuclear issues therefore requires us to “[stay] with the trouble” (Haraway, 2016). NIC exhibits play on messiness to a degree. Exhibits may appear structured and ordered on the surface yet contain an underlying messiness. For example, NIC exhibit NIC/GD/001, Thinking Inside the Box is partly about the containment of radioactive material and presents as an archive box placed neatly on a trolley. However, despite its tidy appearance, all is not what it seems. The audio track emanating from within the box will not be contained and the sound leaks out into space, aurally contaminating the immediate surroundings.

Non-Sites.

The Nuclear Information Centre draws heavily on Robert Smithson’s sculptural Site/Non-Site [4] dialectic which addresses the relationships between real, external sites and metaphorical representations of those sites within alternative physical or virtual (to bring it up to date) locations. “It is by this three dimensional metaphor that one site can represent another site which does not resemble it—thus The Nonsite”. (Smithson, 1968).

For example, What about the Waste? as referenced earlier, is conceived as a 3-dimensional or sculptural “factsheet” about the future site and function of a geological disposal facility. The work itself is an amalgam of 3 elements: an abstracted version of the future but as yet unknown site, the generic, graphical shape of radioactive decay in the form of half-life curves and the empirical milestones associated with the projected project timeline. Perhaps we can even take Smithson one step further and think of this exhibit being a non-site of a non-site given that a GDF has yet to exist at a specific location.

Numbers.

Numbers carry weight and influence and are easily processed by an audience. We know what small and large numbers look and sound like. Strategically, numbers are useful as they can be used to sound authoritative, precise, and vital, yet can also be suitably abstract, and seemingly justify themselves without the need for a detailed breakdown. For example,

We are committed to building the first new nuclear power station in a generation at Hinkley Point C in Somerset, which will provide 3.2 GW of secure, low carbon electricity for around 60 years to power around 6 million homes and provide 25,000 job opportunities. [5]

Repetition.

Repetition is a multi-functional linguistic, audio, and visual tool. It can be used for emphasis, emphasis, emphasis, and as a potential route towards normalisation in that seeing, hearing, or reading the same thing over and over, can create subtle shifts in perception over time. Deleuze wrote about repetition in terms of difference in that each instance of repetition is a unique occurrence in space and time. (Deleuze, 1968, 1994, 2014). The spaces between each repetition are also equally important as these define the nature of each repetition and this intertwined effect can become almost abstract, affecting our responses. This is tested in two NIC audio exhibits: NIC/NW/006, Neither Confirm Nor Deny [6] and NIC/NS/001, When you hear this sound [7] where the audio shifts gradually over time or becomes blurred.

Safety.

At the entrance to each of its UK sites, EDF Energy displays a message carved into a block of granite proclaiming, “Nuclear Safety is our Overriding Priority”. At face value this is commendable given the potential nuclear hazards at stake. However, the concept of safety can be slippery too. What if we were to announce “Nuclear safety is our Overriding Priority” but this time in the context of nuclear weapons and deterrence? Suddenly concepts of safety seem more problematic.

Strategic Language.

Strategically located and considered words within text and audio can work subliminally in shaping our responses. For example, globally agreed solutions for the safe disposal of radioactive waste carries more weight than just agreed solutions for the safe disposal of radioactive waste. Swapping words around and making questions from statements can also be a simple, effective textual reprocessing device.

Geological Disposal is the right thing to do for today’s society and for future generations.

Is Geological Disposal the right thing to do for today’s society and for future generations?

Is Geological Disposal the right thing to do for today’s society and for future generations?

Subversion.

The dictionary definition of subvert is to undermine the power and authority of (an established system or institution). However, this can be approached in a range of ways, including strategies that appear quite subtle but all of which require a degree of intent. Subversion is unlikely to happen by accident and generally requires considered thought. In terms of information, we could think of it as linguistic engineering, the re-shaping of text or objects to present alternative readings. It is about looking and looking again, always on the lookout for possibilities. How overt does successful subversion need to be? It can be achieved very simply and powerfully by presenting an existing object but slightly out of context. Humour can also be a valuable addition to the subversionist’s toolbox (see separate glossary entry).

For example, the following image is taken from the cover page of an Office of Nuclear Regulation (ONR)[8] document. However, all is not what it seems as two additional words have been inserted which match the existing font exactly. At first glance it could be an image of the genuine document but through the careful addition of just two words the document has been subtlety subverted in ways that might not be immediately obvious.

Figure 6. Office for Nuclear Regulation (ONR) – Licensing Nuclear [Information Centre] Installations, 2022.

Other organisations also operate within the realm of subtle subversion as can be seen from the Eventbrite screenshot below:

Figure 7. Edinburgh Environmental Humanities Network – Eventbrite listing.

Trust.

Official information understandably projects an authoritative voice but, importantly, it also asks for our trust. If something looks or sounds plausible and comes from a recognisably official source, are we more pre-disposed to be accepting of it? At a GDF [9] community engagement event I attended in Lincolnshire in the summer of 2022, a Nuclear Waste Services engagement officer explicitly stated, “We’re building relationships. We are interested very much in trust”. Official information wants to be trusted.

To what extent do you trust the Nuclear Information Centre?

Notes

[1] For example, the following document lists almost three pages of abbreviations and acronyms (pp. 33-25). https://assets.publishing.service.gov.uk/government/uploads/system/uploads/attachment_data/file/1037478/20211129-LAESI-Ed12-MHCLG-Tweak-final.pdf (Accessed: 07 November 2022).

[2] https://www.gov.uk/government/publications/uk-nuclear-deterrence-factsheet/uk-nuclear-deterrence-what-you-need-to-know

[2] Dr Ele Carpenter is an academic, curator, and convenor of the Nuclear Culture Research Group, established as a forum for practitioners and scholars within the arts and humanities to share information, projects, and events, situated within the realm of nuclear culture. https://nuclear.artscatalyst.org (Accessed: 23 Nov 2022).

[3] https://nuclear.artscatalyst.org/content/perpetual-uncertainty-z33

[4] https://holtsmithsonfoundation.org/provisional-theory-nonsites (Accessed: 22 Nov 2022).

[5] https://www.gov.uk/government/news/nuclear-energy-what-you-need-to-know (Accessed: 21 Nov 2022).

[6] https://nuclearinformationcentre.org.uk/Neither-Confirm-Nor-Deny

[7] https://nuclearinformationcentre.org.uk/When-you-hear-this-sound

[8] The ONR is the official nuclear regulator in the UK

[9] Geological Disposal Facility. (The UK government is currently engaged in the process of looking for a site for the permanent disposal of the country’s higher activity radioactive waste). Nuclear Waste Services (NWS) are the government agency charged with administering the process).